Conning a Caveman:

What Can Evolutionary Theory Tell Us

About Modern Cons?

By Andres Munoz

You’re walking down a quiet street during a trip abroad. A woman approaches you with tears rolling down her eyes and tells you between sobs that her son was in a car accident and that she doesn’t have enough money to cover the medical bills. She pulls a picture of a teenage boy out of her purse and shows it to you. “This is my son Jack. He’s always been such a good boy, so responsible. I can’t believe such a tragedy could happen to such a good boy.” She explains that she’ll be getting her next paycheck in a few weeks, but that she needs to put down a $500 deposit by the end of the day for the doctors to begin treatment.

A man approaches with a concerned look on his face. “I’m sorry, I couldn’t help but overhear. Here, take this. Sorry, I only have $200 at the moment. I wish there was more I could give.” The distraught mother takes the money and exchanges phone numbers with the man. “I’ll call you as soon as I get my next paycheck and I’ll pay you back. Thank you so much for your kindness, I guess there are still good people in this world.” Then, the mother turns to you. “Is there any money you could spare?” You have $500 cash on you for trip emergencies, so now you must ask yourself whether you want to part with some of it and give it to this person you just met.

Would you give some of your money to this stranger? If your answer is yes, then you would have fallen victim to a con, or confidence artist. There was no car accident. The person asking you for money didn’t even have a son. And the kind stranger who gave $200? He was also part of the scheme, all carefully engineered to trick you into giving your money away. If you think you wouldn’t fall for it, you might be wrong. Many people think themselves invulnerable to cons. It’s easy to think that the victim of a con must have been incredibly gullible and that a similar tragedy would never befall us because we’re too smart. However, no matter how smart, people have evolved mechanisms for trust that can leave them open to being conned.

Because trust is beneficial in many situations, we have evolved to be trusting and cooperative animals. Trust allows us to coordinate with other people to overcome obstacles that would be insurmountable and to obtain benefits that would be inaccessible to us as individuals. For example, imagine that you live during the time of our hunter-gatherer ancestors and that you encounter a mammoth. You might not be able to take down the mammoth by yourself and you might even end up dead if you try. In contrast, you might be successful at hunting the mammoth and obtain a wealth of resources and meat if you work together with a group of hunters, courtesy of your ability to cooperate and trust other people. However, trusting others also makes us vulnerable to exploitation. After taking down the mammoth, one of the hunters might decide to keep the resources to themselves and not share them with you. To prevent this from happening, you would need psychological mechanisms that would allow you to identify situations in which you are being taken advantage of. Cons are the modern world’s version of this ancient tension between people who might try to exploit others for their own selfish gain and cooperators who need to identify and protect themselves from exploitation.

Specifically, cons are situations in which a perpetrator builds trust, through the use of deceit, in the pursuit of some benefit for the con artist and at a cost to the victim. In my research, I’m looking at the vulnerabilities in our ability to detect cons. We are vulnerable to cons in some situations, but this doesn’t mean that people should stop trusting others. On the contrary, I believe that by understanding the science behind conning, we can better equip ourselves to not get taken advantage of by con artists while still allowing us to get the benefits of trusting others.

Many cons can be classified into two types based on the type of motivation that they target. One type of con exploits your motivation to acquire resources. This motivation is ingrained in our evolved psychology because it helped our ancestors to survive and reproduce. It’s not difficult to imagine how our ancestors might have benefitted from being motivated to acquire resources. This resource acquisition motivation helped our ancestors to obtain food, water, wood, and other resources that would have been essential for survival.

Cons that exploit your motivation to acquire resources typically involve convincing victims to invest in a bogus opportunity that would supposedly make them rich fast. An example of this type of con is known as the fiddle game. This con involves two con artists. Imagine you’re sitting in a restaurant. The first con artist walks into the restaurant with a rare-looking violin. Then, the con artist claims that he has forgotten his wallet and leaves his violin as collateral to the restaurant while he goes to retrieve his wallet. In the meantime, a second con artist approaches you and claims to be a musical instrument dealer. He explains that he noticed the violin that was left as collateral and that it is a rare and expensive violin. Then, he says that he would like to purchase the violin and that he would be willing to pay thousands of dollars for it. The con artist notices the time, excuses himself by saying that he’s running late, and hands his card with a fake phone number to you. The first con artist then returns with their wallet. At this point, you might be tempted to offer the con artist with the violin hundreds of dollars for the instrument, hoping to sell it to the musical instrument dealer for thousands of dollars. If you decided to buy the instrument, you’d be stuck with a cheap violin and a fake business card from a fake violin dealer.

In the fiddle game con, the victim is someone who wants to make money quickly. Therefore, activating a person’s greed is one mechanism by which this con can take place. Greed implies that the victim has a strong desire to possess more than they need, which would lead them to jump on any opportunity to make more money regardless of their financial situation. However, greed is not required to be vulnerable to this con. Often, victims of cons such as the fiddle game are people who are in dire financial situations and are desperate to make money, such as people with significant debt or people who find that they don’t have enough money to support their families.

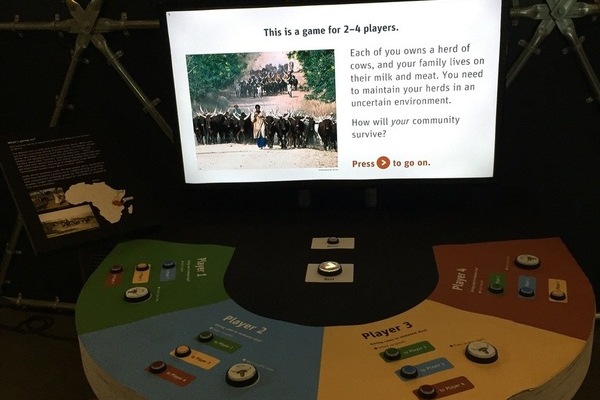

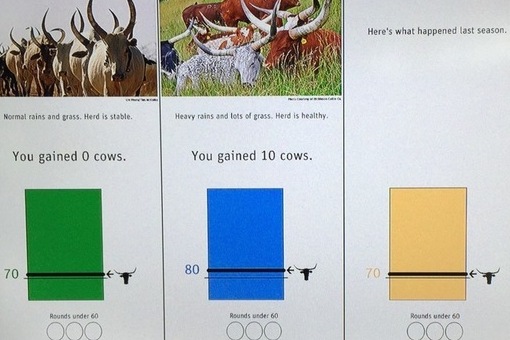

The second type of con exploits your motivation to help people in need, such as the con described above in which a concerned mother needed money for her son’s medical bills. The motivation to help people in need is also a part of our evolved psychology because it was useful for our ancestors. Research by the Human Generosity Project suggests that helping each other in times of need not only feels morally correct, but can also have great benefits for the helper (Aktipis et al., 2016). For example, Maasai pastoralists in East Africa have relationships known as “osotua,” which translates as “umbilical cord.” Osotua partners help each other in times of need without an expectation of repayment. These relationships allow the Maasai to survive when they experience unexpected losses due to events such as droughts. Research by the Human Generosity Project suggests that these kinds of relationships, in which risk is pooled to guard against unexpected catastrophes, are common across many societies (Cronk et al. 2019).

Even in our modern environments, it pays to have people that you can rely on during times of need. For example, you might know somebody whose house burned down during a fire in California or someone who lost their house after a hurricane in Florida. In both of these terrible situations, many people turned to their friends and family for help in their time of need. Thanks to people’s generosity, many victims were able to endure the difficulties caused by these catastrophes. Times of need in our modern environment are not limited to natural disasters. For example, you might know someone who unexpectedly lost their job or who got sick and had to ask for help from their friends and family.

Given the benefits of helping each other in times of need, it’s not surprising that we are often motivated to help others. However, by helping others, we make ourselves vulnerable to greedy people who lie about being in need in order to obtain resources from us. Cons in this category usually involve presenting the victim with a fake emergency and asking the victim of the con for help. For example, have you ever been at a gas station and had a stranger approach you to ask you for gas money? Or claim that their car is stranded somewhere else and that they need money to pay a tow truck? You might feel inclined to help the people in these situations, but sometimes these requests for money are based on lies. This type of con exploits our cooperative nature and is particularly destructive; it could lead us to become more suspicious of people in need and reduce the amount of helping even in situations when the need is real.

Sometimes, the exploitation of peoples’ desire to help those in need can be especially insidious. In 2018, you might have seen on your social media feed a story about a homeless man who gave the only money he had to a woman who needed gas money to get home. The woman who was helped by the homeless man started a social media campaign to raise money for him. Would you have contributed? If so, you would have fallen victim to a con. The woman who set up the page gave little if any money to the homeless man she was supposedly raising money for. The con artist spent almost $400,000 raised through GoFundMe page on things such as gambling at casinos. And the heartwarming story about the homeless man giving his last few dollars to help a stranger? It was made-up. If you want to read more about this story, click here and here.

These kinds of cons can challenge our faith in humanity and make us question our own generous impulses. But are we completely vulnerable in the face of con artists or do we have some way of defending ourselves? Some of my recent work suggests that we have the ability to tune into situations where we might be exploited and detect cheating on norms such as “don’t ask for help unless you are truly in need.” I have found that we appear to have evolved alarm systems that allow us to detect when people are being greedy. This can give us some hope. But it is also important to appreciate that these alarm systems are not perfect, and we often face information and time constraints that make it particularly difficult to determine whether someone is truly in need or not. More research is needed to understand how each type of con operates, but classifying cons based on the different motivations that they exploit is a useful first step that can help to illuminate the weaknesses in our defenses.

In addition to classifying cons based on the motivations that they exploit, it is useful to consider how our current environments might be different from those of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. The evolutionary mechanisms that protect us from exploitation are likely to be designed, at least to some extent, to function well in an environment that was radically different from our current environments. Imagine going back in time and living among our hunter-gatherer ancestors. A man you don’t know approaches you and tells you that he doesn’t have enough meat to feed his family and asks you for some meat. You just returned from a successful hunt, so you have some meat to spare and you decide to give the man some meat. What would it take for this man to disappear from your life forever after receiving that meat? He would probably have to abandon his small band of hunter-gatherers, which would pose great risks. In fact, you could probably ask around the camp and acquire information about the man fairly easily, which would allow you to retaliate if you find out that you have been conned.

Now, imagine that you’re back in the modern world and you get a desperate message through social media asking for money for an emergency. You decide to send the money they were asking for. You later find out that the person asking you for money was not who they said they were. What would it take for this person to disappear from your life forever after receiving the money? They already have – there may be no way to track or follow up with this person. In contrast, cities with millions of inhabitants, along with modern transportation methods, have made it easier than ever for a con artist to vanish into the crowd or move to a different city after carrying out a con.

Many opportunities for conning have emerged with the invention of modern modes of communication such as the internet. These increase the physical distance between victim and perpetrator and make it relatively easy for perpetrators to remain completely anonymous even after their lies have been discovered. Our modern environments also allow for boundless accumulation of wealth, which makes the potential payoffs for cons greater. In addition, wealth is often much easier to hide in our modern environments than it was for our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Therefore, it’s more difficult than ever to truly know whether someone is in need or not. Con artists in our modern environments face fewer risks and greater potential rewards from exploiting our natural desire to help people in need, and all we possess to defend ourselves against such exploitation are cognitive mechanisms that are built for a different social world than the one we now live in.

Let’s return to the mother who was asking for money for her injured child. In this case, the con artists are targeting our evolved motivation to help those in need. Moreover, the con artists are taking advantage of the fact that they could vanish relatively easily after the con given the features of our modern environments. They could walk into a crowd of people or take a plane to another city and hide from you without much effort. Meanwhile, your line of defense consists of mechanisms for detecting greediness that were useful to our hunter-gatherer ancestors, but that might not be properly equipped to deal with the modern world. How could you tell whether the person asking for money is actually in need if you can’t see their bank account? It might seem hopeless. We are more vulnerable than ever to cons, which is why more research is needed to understand our weaknesses and the ways in which we might be able to overcome them.

While we wait for more research to help us better our defenses, keep in mind that cons are based on deceit. If you ask for enough information, eventually the con will fall apart. In the case of the mother asking for money for her child, imagine that you ask for the name of the doctor that is treating her son. The con artist can’t memorize every possible detail beforehand, so she might be forced to make up a name. Later in the conversation, you casually ask what the name of the doctor was again. The con artist might be unable to recall the name of the doctor that she gave you earlier and give you a different name or realize that you’re onto her and give up the con. Moreover, the more details the con artist is forced to produce, the more likely it is that the lies will be inconsistent and the fraudulent nature of the request will be revealed. For example, imagine you ask the con artist to describe the accident and she tells you that her son hit his head really hard against the car door. Later, you ask about her son’s injuries and she mentions broken ribs but says nothing about a head injury, which would be inconsistent with her earlier emphasis about her son hitting his head.

Another aspect of conning that you should keep in mind is that the con artist’s goal is to get you to part with your money. If the con artist is trying to get your money by asking for help, remember that help can often come in other forms that are not monetary. If you offer help that doesn’t involve giving money, the con artist is likely to turn it down or even get frustrated and insist on asking you for money. Let’s return to the scenario of a mother asking for money for her injured child. If you’re a lawyer, offer legal advice. If you play the guitar, offer to visit her son and play a song to make him feel better. There are countless ways to lend a hand that don’t involve writing a check. Therefore, there is no need to give up your generous nature because of a fear of getting conned.

If you think you might have been a victim of a con, or you just want to learn more, click here for a useful resource that describes some of the most common types of cons and how to report and protect yourself from each.

References (available on our publications page)

Aktipis, C. A., De Aguilar, R., Flaherty, A., Iyer, P., Sonkoi, D., Cronk, L. (2016). Cooperation in an uncertain world: For the Maasai of East Africa need-based transfers outperform account keeping in volatile environments. Human Ecology.

Cronk, Lee, Colette Berbesque, Thomas Conte, Matthew Gervais, Padmini Iyer, Brighid

McCarthy, Dennis Sonkoi, Cathryn Townsend, and Athena Aktipis. 2019. Managing risk through cooperation: Need-based transfers and risk pooling among the societies of the Human Generosity Project. In Global Perspectives on Long-Term Community Resource Management, Ludomir R. Lozny and Thomas H. McGovern, eds. Springer.

SHARE THIS PAGE: